In 1956, America was confident it knew what music should look and sound like. Songs were polite. Performers stood still. Television smiles were carefully rehearsed. Then a 21-year-old former truck driver from Memphis stepped into that orderly picture and shook it to its core. His name was Elvis Presley, and within months, the country would never hear—or see—music the same way again.

By the time the calendar reached mid-1956, Elvis was no longer a regional curiosity. He was touring relentlessly, crisscrossing the nation with dozens of shows that left audiences stunned and divided. In theaters and auditoriums from the South to the Northeast, the reaction followed a familiar pattern: disbelief, excitement, and then something close to hysteria. Young people felt seen. Older generations felt unsettled. Something powerful was happening, and no one could quite agree on what to call it.

The tension reached a breaking point when Elvis appeared on national television.

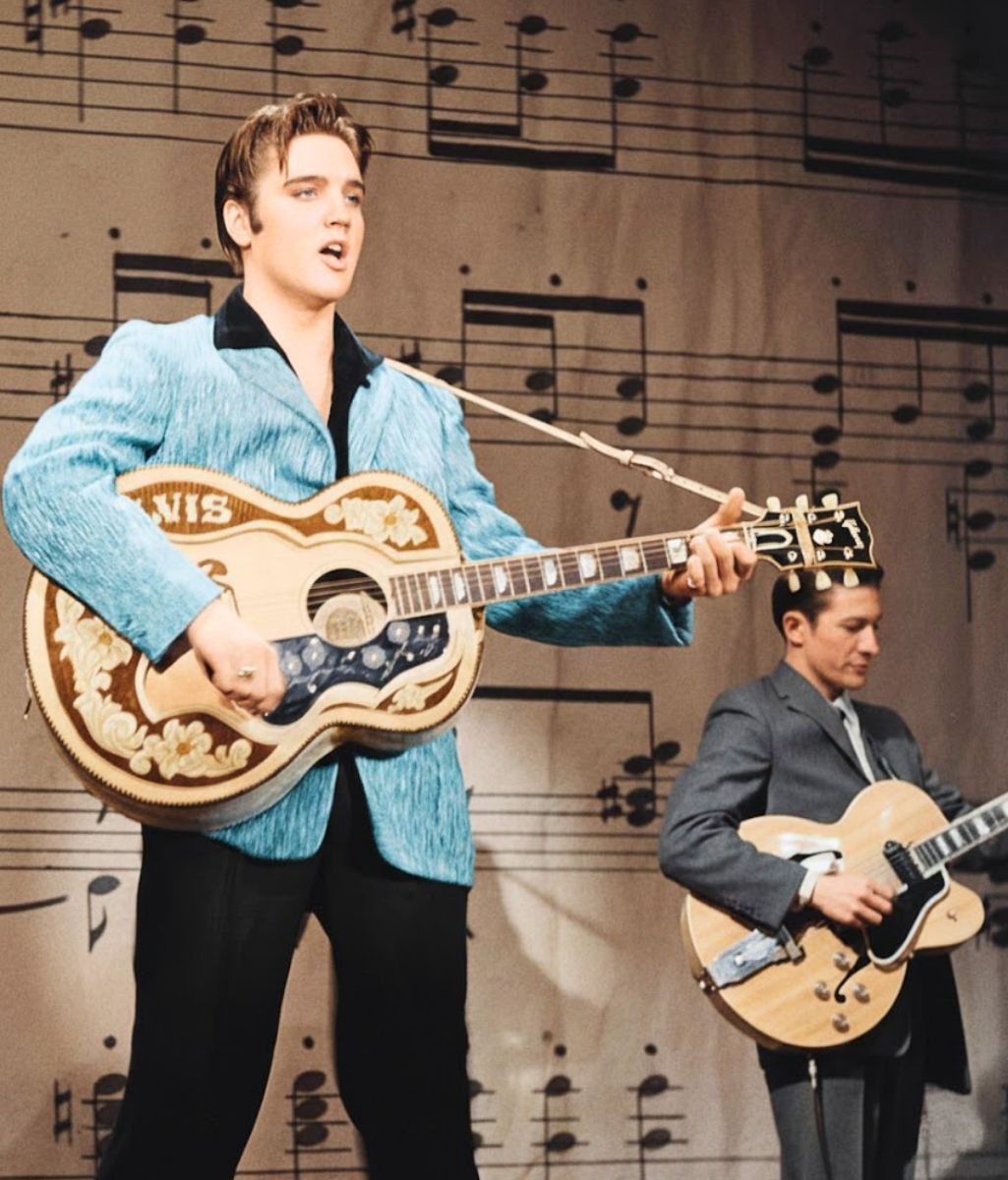

His performance on The Milton Berle Show became an instant flashpoint. As he sang, his body moved with the rhythm in a way American television had never presented before. It was not planned provocation. It was instinct. Yet the effect was explosive. Viewers flooded networks with complaints. Newspapers debated morality. At the same time, young audiences screamed, laughed, and felt a rush of recognition they could not explain.

What frightened critics was not noise or volume—it was freedom. Elvis did not ask permission to move the way the music demanded. His confidence felt contagious. For the first time, millions of teenagers saw someone their age commanding attention on his own terms. Music was no longer something you simply listened to. It was something you felt in your body.

If the Milton Berle appearance lit the fuse, The Ed Sullivan Show detonated the moment. When Elvis finally appeared on Sullivan’s stage, the nation gathered in living rooms, split almost evenly between alarm and anticipation. Parents watched with folded arms. Teenagers leaned forward, breath held.

The cameras famously limited what could be shown, but it no longer mattered. The energy alone was enough. Elvis sang with focus and intensity, his presence radiating through the screen. Young viewers wept openly. Some screamed. Others simply stared, overwhelmed by the realization that culture itself was shifting in front of them.

For many parents, the moment was unsettling. It felt like a loss of control, a challenge to values they believed were fixed. For their children, it felt like discovery. Elvis represented possibility—a world larger than rules, quieter expectations, and inherited limits. He did not preach rebellion. He embodied it by existing fully as himself.

By the end of 1956, the change was undeniable. Music sales soared. Hairstyles changed. Fashion loosened. Language shifted. Elvis Presley had not merely succeeded as an entertainer; he had exposed a generational divide that could no longer be ignored. Rock ’n’ roll, once whispered about, now stood at the center of American life.

What made Elvis’s rise so powerful was its speed and sincerity. He was not a calculated product of controversy. He was a young man responding honestly to sound, rhythm, and feeling. The reaction—outrage and joy in equal measure—revealed how ready the country was for something new, even if it did not yet know how to accept it.

Looking back, 1956 stands as a cultural fault line. On one side, tradition. On the other, transformation. And standing at the center was Elvis Presley, moving to a beat that refused to stay contained.

He did not conquer America with force or argument.

He conquered it with rhythm.

And in doing so, he ignited a rebellion not of anger, but of expression—one that still echoes every time music dares to move more than just the ears.